Fig.1 Fig.2

Admittedly, the photograph above left was not taken yesterday (it’s c.1998) but it is still considerably more recent than the Staffordshire pottery figure group in my hands and which is shown in more detail to the right. The article that follows was originally published in The Northern Ceramics Society Newsletter No. 103, September 1996 after I had been encouraged both to join and submit my work by Pat Halfpenny, then Keeper of Ceramics at the City Museum and Art Gallery in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent (Fig.3).

Fig.3

The article was prepared at the time I was Founding Curator of the Johnston Collection, a private house museum established following the passing of William Robert Johnston (b.1911-d.1986) and a treasure-trove of 18th and 19th century fine and decorative arts. Between 1990 and 1998 I researched and catalogued much of the collection, specialising in the English porcelain and pottery about which I wrote and lectured extensively in Melbourne, regionally and interstate.

The article was published again in The Australian Antique Collector the following year before I re-worked and expanded the article and presented it to a Sydney ceramics dealer who kindly published what I consider to be the definitive version to date. It is this version which follows…

The spill vase figure group dates to c1850-1855 and features in Rear Admiral P.D.G.Pugh’s classic tome(1) in the Miscellaneous Section (Section 1) on pages 524 (Plate 18, Fig.47) and 526. It is a typical Victorian expression of both heroism and sentimentality with other known variations showing dogs protecting children from eagles and snakes. Whilst no firm source appears yet to have been found for this particular group, the following is my suggestion that may warrant consideration.

In fact, two possible sources have been found. Firstly, a publication translated from the original German(2) includes a silhouette depicting a Newfoundland pulling a child from a river or pond. It accompanies a verse titled The Grateful Dog, one of a series of verses contained therein illustrated with elaborate hand-cut silhouettes (Fig.4). The dog concerned is not identified but it is surely just one of many typically faithful and heroic Victorian canines.

Fig.4

The second and more likely source, in my opinion, is a painting titled The Rescue by Miss M.A Barker. My discovery of a lithograph engraved by R. Forse at Werribee Park Mansion, Victoria, Australia in 1994 led to the possible existence of an original, albeit seemingly lost, oil painting. I found and purchased another example of this lithograph a couple of years later in rural Victoria (Fig.5)

The print shows a Newfoundland in the act of pulling a child by its clothing from the water of a river or pond. A partly submerged toy sailing boat can be seen at the lower right. There is no indication of the location of the scene.

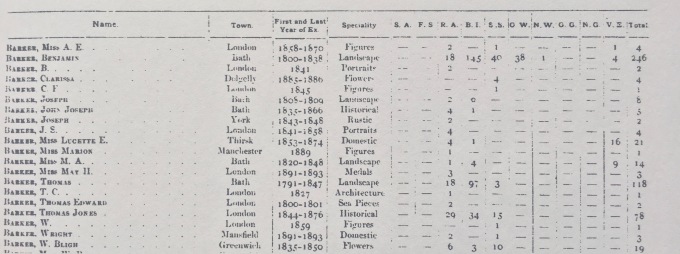

Marianne A. Barker (b.1802-d.1888) was the daughter of Benjamin Barker (b1776-id1838), one of four sons of Benjamin Barker Snr. (b. c1720-d.1793). The family of painters became known collectively as The Barkers of Bath(3). Most produced landscapes in the manner of Gainsborough, who had resided in Bath for some fifteen years, although Benjamin Jnr. has been referred to as “the English Poussin” and Thomas Jones Barker (b.1813-d.1888) was a celebrated portraitist and painter of historical scenes. Marianne married naval officer Captain George Wallace in 1826 and is known to have exhibited a total of fourteen works at, amongst other, the Royal Academy and the British Institution between 1820 and 1848.

Fig.5

The one exhibit at the Royal Academy recorded in the list below was titled “85 Composition”(4). Those exhibited at the British Institution were landscapes titled variously “Near Box, Wilts” (x 2), “Near Bath” and “Scene from nature”(5) (Fig.6). At he time these works were submitted, Marianne resided with her parents Benjamin and Jane at Smallcombe Villa on the south-east outskirts of the city of Bath. Benjamin built the house shortly after 1814 when he purchased the land with his brother-in-law James Hewlett the flower painter. It was a plain house “perfectly square in plan with an M-shaped roof and rendered in Roman cement”(6). The seven acres of picturesque-manner garden was not only well-established by 1817 but also sufficiently well known to attract a visit by Queen Charlotte in that year.

Fig.6

Marianne’s mother died in 1825. Following her marriage a year later, Marianne moved to Totnes in Devon where Benjamin joined the couple in 1833.

In an interesting ceramics twist, Marianne’s uncle Thomas (b.1767-d.1847) had a number of his most successful images (including The Old Woodman and Old Tom) “copied upon almost every available material which would admit of decoration: Staffordshire pottery, Worcester china, Manchester cottons and Glasgow linens.” (7). One can see the former image painted on one of a pair of Flight, Barr and Barr spill vases of c1825-1830 (8). There appears to be no connection, however, between the Barkers under discussion here and the John Barker who excelled at shell painting at Flight’s between about 1819 and 1840.

I around 1845 John and Rebecca Lloyd of Shelton produced a pair of figures one of which was modeled on Barker’s Woodman. It was a far from successful transition, however, with the figure profusely gilded and Barker’s ferocious lurcher dog transformed into a toy poodle! (9)

Returning to the Rescue Dog figure, the version illustrated in Figs.1&2 in the author’s collection measures 20.5cm the same height as the example in Pugh’s book. Two further examples I worked with at the Johnston Collection measured 20.5cm and 19.5cm giving a maximum comparative variation of a centimetre. They have each exhibited the minor variations in painted and applied decoration that one would expect from such mass-produced figures.

The main body of the figure was produced in a traditional two-part press mould with seperate moulds being employed to produce the dog’s head and the figure of the child.

At the child’s feet can be seen the moulded representation off the stonework arch of a bridge while at the head is a short flight of steps*. The common use of applied shredded clay has been used at various point on the tree trunk and across the front of the group. This is commonly referred to as “moss” or “parsley”. Nice, soft gilding (Best Gold) has been applied to the mouth of the spill vase, the tree trunk, around the neck of the child’s garment and across the front of the base. This particular example displays fairly minimal colouring; others show more extensive brown enamels applied to the tree trunk.

The placement of the child’s arms at either side of the dog’s head in this particular example clearly corresponds with the positioning in the lithographic image. The placement of the arms in three other examples sighted have all extended alongside the body and/or crossed at the waist. Another example of the Rescue Dog appears in a publication (10) in which, unfortunately, Marianne’s surname is misspelled. However, in this example the child’s arms are also raised either side of the dog’s head.

Additionally, all of the examples I have seen are designed to face left but it seems likely that such spill vases, made to sit either end of a mantlepiece, are made as pairs and that an example facing to the right exists somewhere. Spills were tightly rolled lengths of paper, the tops of which were sometimes dipped in wax and used to take a light from an open fire to light a pipe or candle.

I have more recently located another lithograph that would appear to lend my suggested source further support. Fig.7 shows a printed image titled Lost and Saved (published by McGready, Thomson & Niven, Glasgow) after an original in oils by Thomas Jones Barker (b.1813-d.1888). Thomas was a first cousin to Marianne. This latter work is very reminiscent of Sir Edwin Henry Landseer’s (b.1803-d.1873) work Saved. Nevertheless, it shows an interesting thematic predilection for at least two members of the Barker family and a theme that was to continue to be popular for many more years both with painters and exhibition-goers.

Fig.7

Finally, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh has provided me with a remarkably similar image on the lithophane shade of a candleholder. The shade is formed from biscuit porcelain and the candleholder and ornate stand are of cast iron. It is thought to be of either German or Austrian manufacture and to date to c.1835-1844. Unfortunately, I am unable to reproduce the image here but it was one of some two hundred and fifty objects included in an exhibition called Light! The Industrial Age 1750-1900, Arts and Science, Technology and Society in 2001 (11).

The dating of the lithophane is interesting. If Marianne Barker’s painting The Rescue is, indeed, the source for this Staffordshire figure group, the dating of the latter may need to be adjusted by a few years to, say, c.1845-1850. The lithophane image could also suggest another source altogether but, whilst I am open-minded, I am more comfortable with an English painting being the source for what is, after all, a quintessentially English ceramic art form.

*These moulded details can be found on many Staffordshire figures but were also integral to the picturesque ornamentation incorporated into the gardens at Smallcombe Villa – “These (water features) are linked by cascades and rockeries, spanned by stone bridges and surrounded by gravel paths and flights of stone steps” (12). A flight of fancy found me imagining discussions between modeller and painter resulting in these details, with which Marianne would have been so familiar at her family home, being included.

© Harry F. Blackburn 2005 (2018)

1 P.D. Gordon Pugh, “Staffordshire Portrait Figures of the Victorian Era”, Antique Collectors Club, 1987

2 “Karl Fröhliches Frolicks With Scissors and Pen”, Joseph, Myers and Co., London, 1860, (translated by Madame de Chatelaine)

3 Philippa Bishop and Victoria Burnell, “The Barkers of Bath”, Bath Museums Service, Bath City Council, 1986

4 Personal correspondence, Royal Academy, London, 08/11/1995

5 Algernon Graves, “The British Institution 1806-1867”, George Bell and Sons, London, 1908

6 Dr Michael Forsyth, “Looking Forwards: The Conservation of a Regency Italianate Villa and Landscape Garden”, Conference Paper, 1999

7 Christopher Wood, “Dictionary of Victorian Painters”, Antique Collectors Club, 1978

8 Henry Sandon, “Flight and Barr Worcester Porcelain, 1783-1840”, Antique Collectors Club, 1992 (Plate 171, page 179)

9 Anthony Oliver, “Staffordshire Pottery The Tribal Art of England”, Oliver-Sutton Antiques, 1989 (Plates 157&158, page 119)

10 Adele Kenny/Veronica Moriarty, “Staffordshire Figures History in Earthenware 1740-1900” Schiffer Publishing, 2004 (pages 182-184)

11 “Veranda” May-June 2001 issue (page 82)

12 Forsyth, ibid

Thank you for this in-depth article. I shared this on Facebook in the group Newfoundland Dog Collectibles

LikeLike

Hello Joan and thank you for your comment. As well as my interest in Staffordshire Figures, my favourite English Factory is Samuel Alcock and I have a small collection of pieces from this firm. Thank you for sharing with your specialist group… all the best!

LikeLike

Thank you for your article, I really enjoyed it..

LikeLike

Thanks for your feedback, David. I had a similar message a couple of weeks ago from Joan Steik of the Newfoundland Dog Group – are you a member? In addition to my interest in Staffordshire Figures I have written about my favourite English Factory, Samuel Alcock and Company and have a small collection of pieces from this firm… all the best!

LikeLike

hi, juST wondering who i can contact regarding the painting for the rescue dog but m barker, we have a copy or original, i would like to know more info about it , thankyou karen

LikeLike

Thanks Karen – interesting! I would love to see a photograph of the picture you have. Can you send an image of it to me at

harryprogger@gmail.com

Once I see it I can advise you further.

Thank you,

Harry

LikeLike

I also have just come in to my possession the same spill vase. Thank you for your article it gave me quite the information. Is it considered a very rare piece?

LikeLike

Hello Jessica. Thank you for your kind comments. I’d like to tell you that the spill vase group is rare but this is not the case. Staffordshire Figures were mass produced and some are more easily found than others. I personally have seen five or six over the years. If you don’t mind me asking, are you comfortable revealing how much you paid? I have had mine for at least twenty years and paid $650.00 Australian dollars at that time. Are you an avid collector? Thanks again for contacting me.

Best,

Harry.

LikeLike